Michael F. Cannon

The Biden administration has announced it will soon increase prices and other obstacles for academics who seek to use federal Medicare and Medicaid data. Academics are protesting the change, claiming it would prevent the sort of research that has improved those programs and could improve them more in the future. Like all interest groups seeking to preserve their government subsidies, these university professors overstate their case.

Still, they have the better argument.

Medicare and Medicaid spend nearly $2 trillion each year to subsidize health insurance and medical care for some 100 million enrollees across both programs. Each year, these programs generate billions of economic transactions in a maelstrom of cash and medicine. (If you think you understand numbers that big, you don’t. Go home.) Even if Congress wanted to ensure taxpayers were getting value for that $2 trillion—and let’s be honest, the evidence there is slim—the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ 6,700 employees would scarcely be adequate.

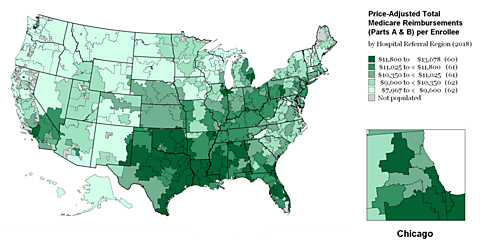

In the normal course of business, though, Medicare and Medicaid generate and collect insane amounts of data. We’re talking data about geography, patient demographics and diagnoses, what medical goods and services enrollees receive and from whom, the prices for those services, and more.

The federal government lets researchers access and use those data. As a stable genius might say, Medicare and Medicaid are so “unbelievably complex” that letting researchers access those data can help “figure out what’s going on.”

And it has! Using those data, researchers have found that as much as a third of Medicare spending is pure waste. Medicare might be spending $300 billion per year on medical care that does nothing to make enrollees healthier or happier. We wouldn’t have known that otherwise.

Researchers have found that—contrary to both left‐wing orthodoxy that Medicare is a swell price negotiator, and right‐wing orthodoxy that Medicare invariably sets prices too low—Medicare overpays long‐term care hospitals to the tune of $30,000 per admission.

In 2022, my colleague Jacqueline Pohida and I published a lengthy article on how Medicare persistently rewards low‐quality care and discourages high‐quality care. We relied almost entirely on research that academics performed with CMS data.

Hundreds of academics have signed an open letter to CMS protesting the change. They say it is unfair to single out academics for these price increases while exempting private firms.

More fundamentally, they argue that increasing the price of accessing these data will reduce the amount of research on, public understanding of, and the performance of those programs.

Those first two predictions are undoubtedly correct. It is far less clear that such research has resulted in concrete benefits. That’s not the academics’ fault. Pohida and I explain that Medicare has “a five‐decade history of rewarding low‐quality care, discouraging high‐quality care, and resisting efforts to improve quality or even to measure quality.”

Even when research has led to changes in policy, it is unclear whether those changes produced tangible benefits. Congress hasn’t exactly cut Medicare spending by a third, for example. The academics note that research showing Medicare subsidizes avoidable hospital readmissions led to the Medicare Hospital Readmission Reduction Program. The HRRP plausibly reduces subsidies for unnecessary readmissions. Yet the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission found the HRRP had no effect on underlying trends in readmissions.

We can forgive the academics for overstating their case. They are afraid of losing a substantial government subsidy on which they are relying so they can contribute to the sum of human knowledge—as well as gain status in their profession, achieve lifetime job security, etc.

But even if this interest group might be conflating its self‐interest with the public interest, government subsidies are generally bad, and one can make a good economic argument against government subsidies even for public goods…it’s still hard not to agree with the academics here.

Taxpayers have a right to know how CMS is spending their money. CMS is collecting these data anyway. Furnishing these data to academics—who are just about the only people trying to figure out what’s going on in these programs—scarcely costs taxpayers anything. CMS should be giving away Medicare and Medicaid data at least as freely as it shovels taxpayer dollars out the door to high‐cost, low‐quality health care providers.

Even if such research has not delivered any tangible benefits yet, at some point it will become extremely useful. Congress cannot keep spending at its current rate. The federal debt is at 95 percent of U.S. GDP and rising. Health care is the only category of federal spending that is growing as a share of GDP. In other words, Medicare and Medicaid cuts are inevitable. When that day comes, it will matter a lot to have research that shows which cuts would inflict the least pain.